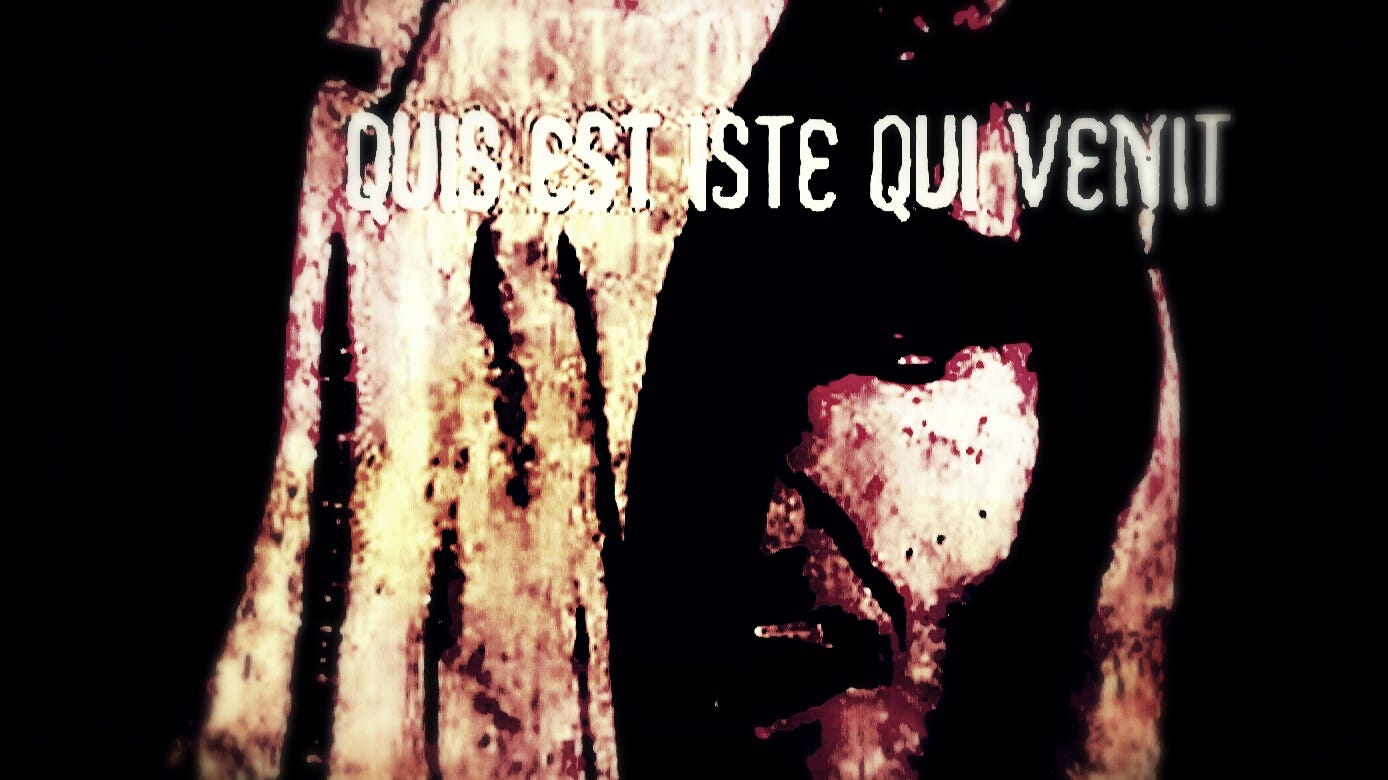

In one of his most famous ghost stories, “O Whistle and I’ll come to you, my lad” , M.R James depicts the rude awakening of a stuffy university professor from his doctrinaire assumptions about the plain, ordinary, materiality of the world, when he finds and uses an ancient bronze whistle and summons a frightening supernatural entity. On the whistle is engraved “QUIS EST ISTE QUI VENIT”- a question in Latin which he mistranslates with regards to implication; his reading is “who is this who is coming?”, whereas the correct version would read “what is- this1! (terror) who is coming”. One question is so commonplace as to appear out of place, and merely odd when found written on an object from the distant past. The other, the question as a warning, is both intelligible and of immense, portentous significance.

The professor casually sounds the whistle and is immediately treated to an uncanny manifestation in sound and vision which begins the collapse of his old dogmatic strictures of belief. The originary “vision” is beautifully and evocatively worded by James, to the effect that (for me as reader anyway) it sounds like a state encountered through meditation –

“He saw quite clearly for a moment a vision of a wide, dark expanse at night, with a fresh wind blowing, and in the midst a lonely figure – how employed, he could not tell.”

The significance of the question(s) is what I take from the story. Martin Heidegger says in “Introduction to Metaphysics” that “the determination of the essence of the human being is never an answer, but is essentially a question”. Questioning directed at ultimate truths rather than relative ones, or at Being itself, is not itself apart from Being. The questioner, and the question in say, “what is being?” or “what is self?” are totally immanent in that which is being questioned; being itself, or, the self. Questioning is therefore an inherent feature of (at least human) Being or Self.

The unfortunate assumption of ordinary consciousness and even a scientific worldview is that this feature – the questioning – is something accidental and ephemeral and that it can and should be ultimately satisfied and annulled. This is not to deny the great value of science, or even the necessary use of inquiry and getting/giving relative answers, information, in daily life. It is rather to recognise the – perhaps unsettling, but also potentially consoling- situation that ultimate questions cannot be answered, and that questioning itself is part of the ultimate in question. Perhaps ultimacy is simply beyond words in itself, whereas words and questions are simply appearances of the ultimate, in a way analogous to how waves and ripples appear in water, but the nature of water is not exhausted in the appearance of waves and ripples.

The question that remains a question without an answer (while pointing to something which is beyond words) is a practice that appears in some traditional Zen literature; in words not unlike the question in M.R James’s2 story, a master asks a prospective student “who is it that speaks?” or “where have you come from?” . These are not directed towards the ordinary, relative world of relative information. “Who” is as much an answer as a question.

A lion roars. A feature of ‘lionhood’ is to roar, or roaring. If Being itself, or ‘Self’ is a lion, perhaps questioning is just the lion’s roar.

“Iste” in Latin is a pejorative

Tathagatha, a title of the Buddha, can be translated as “the thus-come one”

If we ask the question and seek with intent rather than reason, the answer emerges in the Silent Mind from beyond the confines of intellectual understanding, which in itself is limited by relative knowledge. Truth is attained not by thinking but by Will, through supramental faculties that are open to the unknown and the unknowable, so that when the answer is received the intellect lacks the language to speak of such knowledge.